23.8.2023

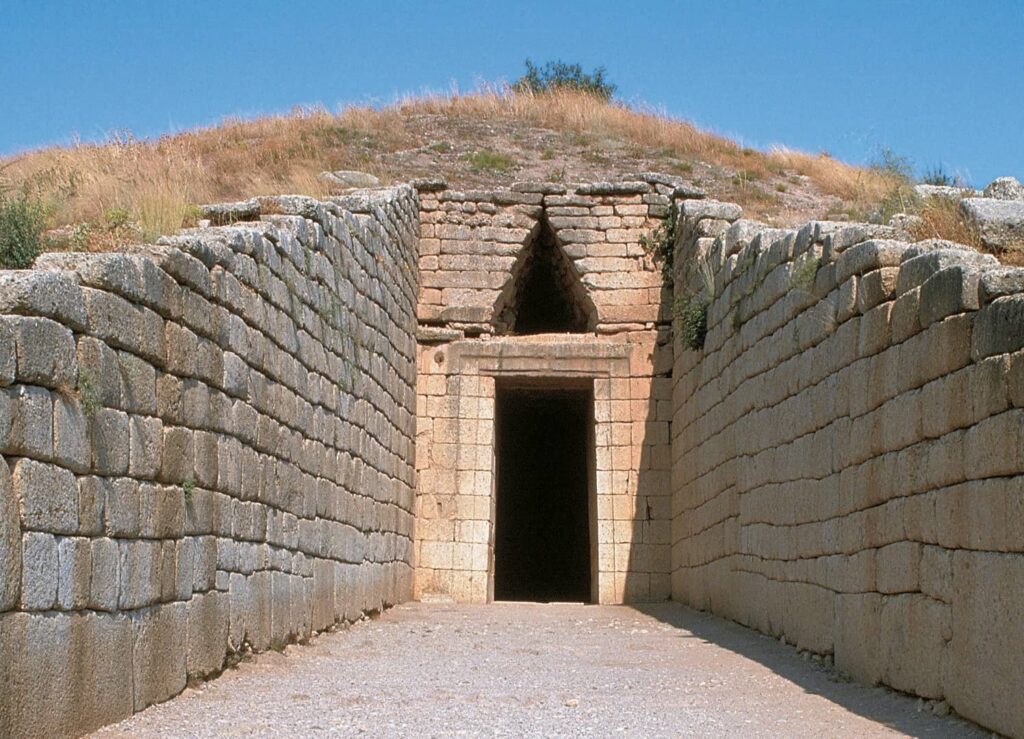

Calabria is one of the first colonies of the Achaeans, the people who preceded classical Greece and founded its customs and perhaps even its genius.

It is therefore natural to wonder about the micro-history of Achaean cuisine as a cultural pick to draw attention to the still closed casket of customs and the highest culture that this ancient people of sailors and warriors left to today’s Calabrians. In fact, nothing is closer to the spirit of a people than the daily lifestyle, which influences the person, in flesh and blood, and subsequently all the social aspects. It becomes interesting to reflect on the legacy of foods, drinks and habits of consumption and preparation of the same that may have remained, in order to then go back through them, even if only in part, to the spirit that accompanied them, which today makes the Achaeans still similar to us and which finally, it unfolded fully in the highest acts of their poetry and literature (Iliad and Odyssey) or of science and the technical arts (from the ancient Achaean doctors to Hippocrates).

SMAF LTD

Explore our products, coming from CALABRIA. Order the food and beverage products that allow you to explore the Mediterranean diet of a remarkable region. Surrounded by two seas and adorned with pine forests, mysterious villages, natural habitats, and rich biodiversity. Discover handcrafted delicacies that embody the soul of the land: sun-ripened fruits, premium olive oils, bold wines, artisanal cheeses, and traditional cured meats, all crafted with passion and authenticity.

ACHAEAN TRADITION IN THE KITCHEN

From the texts found in Mycenae it was possible to reconstruct what the Greeks ate already in the 2nd millennium BC, in the middle of the Achaean era (other sources are the comedies of Aristophanes and some quotations contained in the Deipnosophisti of the erudite Athenaeus of Naucratis). It was a cuisine characterized by frugality, by an economy based on poor agriculture and naturally by the “Mediterranean triad“: wheat, olive oil and wine.

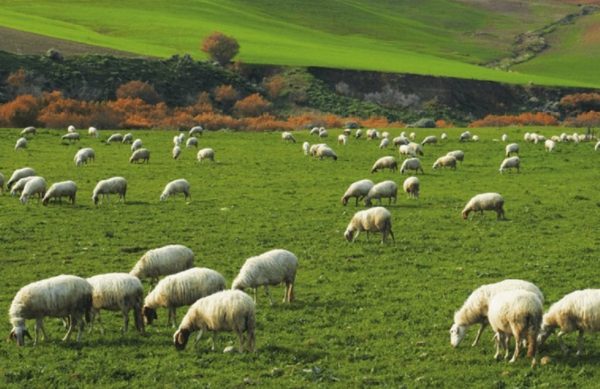

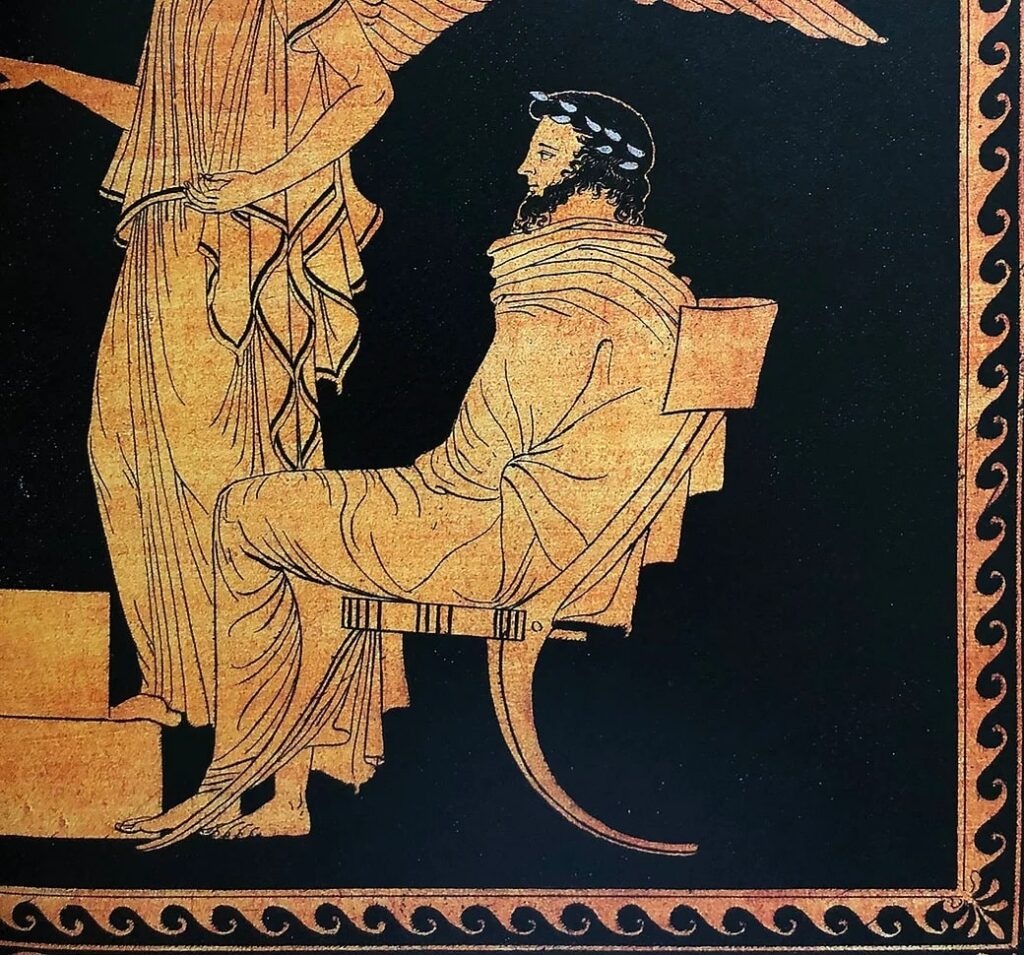

Focaccias were made with barley and wheat; there were chickpeas, broad beans; among the fruits, figs predominated, which were widespread; but the paintings of the vases also show us peaches, apples, pears and pomegranates. In the religious sphere, among the foods offered to the Gods there were tributes (or sacred offerings from the victors of a battle) such as meat, generally obtained from lambs, goats and pigs, but also honey and milk, oil and wine.

In the daily sphere, the ancient Greeks paid increasing attention to nutrition and therefore to cooking, given that various testimonies from philosophers and doctors of the time see, among all Hippocrates, supporting the very strong relationship between the different types of food and the state of health or human disease. In the literary sphere, in the Iliad the heroes are depicted as eating roasted meat (goats, lambs and beef) together with loaves of bread and drinking red wine, the latter very thick and slightly diluted with water and honey.

On the other hand, both the Iliad and the Odyssey rarely speak of goat cheese. An important element in the Iliad was oil everywhere, while fish, fruit and vegetables were almost absent. In the Odyssey, on the contrary, the diet appears more varied, enriched as it is by the cultivation of wheat and barley, combined with vegetables, the consumption of greens and salads. It is only from the fifth century. B.C., however, that fish became the main dish of the Greek diet, while it remained quite rare among the Achaeans.

COOKING AND CONSUMPTION OF FOOD

The typical Achaean cooking method is the embers, although other ways of cooking dishes appear later. In fact, the kitchen tools that will be used later are various and similar to those that are used even today, while in the Achaean period bronze cake pans were used for soups and cakes, pans similar to frying pans and in symposia is very common drinking from the rhyton (a large and impressive mug).

Bread was still cooked with spelled and rye flour. For desserts there was the custom of preparing cakes mixed with figs, honey, milk; at lunch they ate porridge made from cereals, mixed with legumes, cheese, oil and vegetables, so abundant and varied that they deserved the nickname of “leaf eaters” in a comedy to the ancient Greeks.

Instead, it is singular that the olive tree and the vine, often associated with the Achaeans and the Greeks in general as their palm and sign of distinction, were not at all native to Greece. On the contrary, these cultivars came to the Achaeans from the Phoenicians and traders from Syria and Palestine, to whom they were known from more remote antiquity.

Since then, the olive tree had a great diffusion among these remote ancestors, also in Calabria, and was protected by specific laws. It was in fact a sacred tree, with specimens of which the barren lands were reforested. Indeed, it was an absolute obligation to replace the felled trees with new plantings.

On the other hand, wine is often mentioned in Homeric poems and was never lacking in votive offerings, banquets, parties in honor of Dionysus. In a short time it became one of the most exported products: it was transported by sea in large amphorae, or by land in wineskins on the back of mules or donkeys.

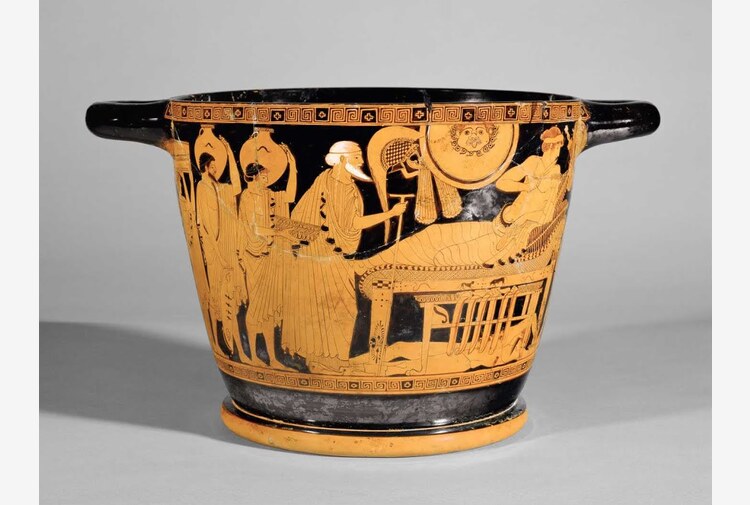

As for the way of consuming food: Achaean ate with their hands, cutlery was unknown on the table, but only kylikes (flared cups) were used, with which they drank the wine. Furthermore, to mix the wine (never consumed pure, but always diluted with water or honey) contained in the craters the ciato was used, a ladle that cupbearers carried hanging from their little fingers and which they also used to measure the dilution of the wine. At home, the Greeks ate three or four meals a day. Breakfast, ἀκρατισμός (akratismos), consisted of barley bread dipped in wine, accompanied by figs or olives, or sweets called τηγανίτης (tēganitēs), cooked in a sort of frying pan τάγηνον (tagēnon, perhaps forerunner of the daily “). Another type of dessert for breakfast was σταιτίτης (staititēs) made of flour or spelled dough. Athenaeus of Naucratis talks about staititas covered in honey, sesame and cheese.

At lunch the people ate quickly (in ancient Greek: ἄριστον, ariston), around noon or in the early afternoon. Dinner (Ancient Greek: δεῖπνον, deipnon) was the main meal of the day and was usually eaten at sunset.

How much are those habits similar to our current ones!

The Greeks normally ate sitting on chairs (klismos), while the beds were used only for banquets. Loaves of flat bread were used as plates, but earthenware bowls were more common. Plates became more refined over time and were sometimes made from precious metals or glass in the later period. The use of the fork was unknown, only knives (shared) were used to cut meat, and spoons for soups and broth.

Sometimes pieces of bread (in ancient Greek: ἀπομαγδαλία, apomagdalia) were used instead of the spoon or as a napkin, to clean the fingers.

FRUITS AND VEGETABLES

The cereals of the Achaeans, seasoned with the opson (in ancient Greek ὄψον), a “sauce or condiment”, were accompanied by cabbage, onion, lentils, marsh cicerchia, chickpeas, broad beans, peas, cicerchia, etc.

This vegetable was prepared in the form of soup, boiled or in the form of puree (ἔτνος, ethnos), and seasoned with olive oil, vinegar, aromatic herbs or the c.d. gáron in ancient Greek γάρον, a fish-based sauce similar to the Latin “garum“.

The poorest inhabitants had to make do with dried vegetables. Lentil soup (φακῆ, phakē) was the typical dish of the worker. Cheese, garlic and onions were the traditional food of soldiers.

Fruit, fresh or dried, and nuts were eaten after a meal. Particularly common were figs, grapes and pomegranates. Dried figs were eaten as an appetizer or with wine. In the latter case, they were often accompanied by roasted chestnuts, chickpeas and beech nuts.

THE WINE

The wine was usually diluted with water. The consumption of akraton or “unmixed wine”, though known as practiced, was rare.

The banquet participant would approach a krater to fill his kylix with wine (already mentioned above, and consisting of a sort of rather small cup or basin), the wine was also used for medicinal purposes, it is said that the Achaean wine could induce abortion.

A rather common object similar to our modern glass was the skyphos, made of wood, terracotta or metal. The kothon is also mentioned in the sources, what became the typical Spartan chalice which had the military advantage of hiding the color of the water from view by trapping the mud in the rim.

For the most common libation, as mentioned, the kylix was used, which at banquets allowed the wine contained in a kantharos (a deep container with handles) to be taken, or the rhyton, an imposing drinking horn, often shaped in the shape of a human head or animal.

THE KYKEON DRINK

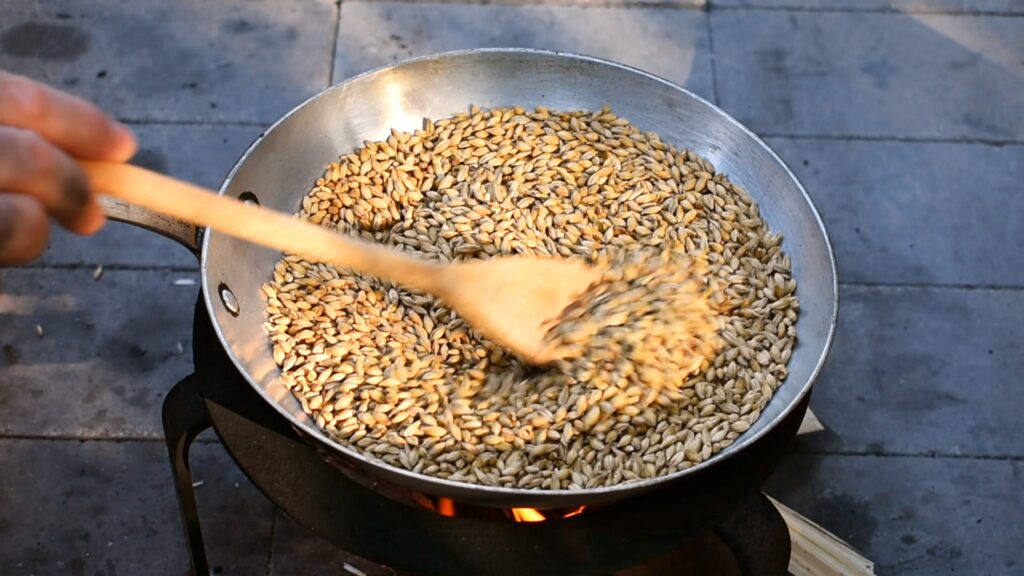

The ancient Greeks also drank the c.d. kykeon (κυκεών, from the verb kykaō, κυκάω, “to shake, mix”), which was both a drink and a meal. It was a porridge made from barley, to which water and aromatic herbs were added. In the Iliad, the drink also contained grated goat cheese, while in the Odyssey, Circe adds honey and a magic potion to it for Ulysses.

In the Homeric Hymns to Demeter, the goddess refuses red wine but accepts a kykeon made with water, flour and mint.

Used as a ritual drink in the Eleusinian Mysteries, kykeon was also a very popular drink, especially in the countryside: Theophrastus, in his characters, describes a rough peasant who, after drinking a lot of kykeon, disturbs the members of the Assembly with his bad breath.

It was also considered a good digestive and was recommended for anyone who ate too much dried fruit.

THE ACHAEAN BREAD

The cereals, the real basis of the Achaean diet, were wheat (σῖτος, sitos) and barley. To obtain bread, a pulp of grains was made by immersion, ground and reduced to flour (in ancient Greek: ἀλείατα, aleiata), then kneaded into loaves (ἄρτος, artos) or focaccia, simple or mixed with cheese or honey. The dough was leavened with the c.d. νίτρον, nitron, i.e. a wine yeast.

The bread was baked in a clay oven (ἰπνός, hypnos) or with embers on the floor.

Barley bread was, on the other hand, more difficult to bake, traces of it still remain today in Calabria, a black and wholemeal bread, apparently rough, but nutritious and heavy (because it is full of water). Even today, 3,000 years later, cheese or honey is added to this black bread. Alternatively the barley was roasted before being milled, yielding a coarse flour (ἄλφιτα, alphita) which was used to make maza (μᾶζα), the staple Greek dish.

The maza could be cooked or raw, as a broth, or made into dumplings or flatbreads.

ACHEAN TRACES IN CALABRIA: BLACK BREAD

In Aspromonte (mountainous area of Calabria, in the extreme south of the region), “u granu jermanu”, or “jermano“, is the dialectal name of rye, which has been cultivated since ancient times by the Achaeans.

With this cereal, worked like barley for bread making, it is possible to appreciate the cultural traces of the aforementioned Achaean passage in Calabria. Indeed, with the use of this ancient Calabrian grain – with many beneficial properties, rich in vitamins, mineral salts and fibers – the Calabrians produce a well-known black bread, with a very rustic taste, low acidity and an intense aroma.

Iermano wheat was widely used throughout the South until the 1950s. With this name (Iermano or in the Jurmano variant) was identified what in Italian was called rye. Re-introduced by the Germans during World War I to make alcohol and bread, Jurmano wheat was well received in Calabria. And today, from Aspromonte to the Sila plateau, there are still some farmers who have been carrying on this cultivar without interruption for over 50 years since the time of the Achaeans themselves!

Meanwhile, since Calabria is a rather mountainous land and therefore subject to very harsh winters, this cultivar, probably of remote Achaean origin, has been able to re-adapt well to our winter climates. Furthermore, it should not be forgotten that, being a very resilient cereal, jermanu wheat even grows in the Arctic Circle and reaches up to 4,000 meters of altitude.

The result is a very tasty black bread, characterized by a remote rusticity. Then, apart from its historical peculiarity and its mysterious past, it is a food that has significant health benefits. Those of Jermanu bread are, mainly, according to various scientific researches, the ability to thin the blood and to prevent arteriosclerosis.

Rye flour, called in the local dialect farina iermano or farina iurmano, often mixed with durum wheat flour, is therefore the main ingredient of a very ancient product, the aforementioned black bread. A bread whose production is very laborious, leavened with sourdough, kneaded in the evening and covered until the next day with woolen blankets. The next day, the preparation begins with strength and effort, the dough of this bread turns out to be thick and viscous. At this point it is cut and cooked for a very long time, about two hours and after cooking it is kept for an equally long time.